There are environmental conflicts that brew slowly and invisibly over decades and suddenly, when certain thresholds are reached, come to light. In the case of the Mar Menor (Region of Murcia, Spain), the first warning sign was in the early 2000s, with the invasion of jellyfish in Europe’s largest saltwater lagoon. Action was taken on the symptoms, but without fixing the causes.

The investments and transformations carried out in the 1970s, with the arrival of the Tajo-Segura water transfer, were aimed at the socio-economic development of the Campo de Cartagena region. For several decades this was achieved, and agriculture and tourism flourished.

From 2016 on, and catastrophically in October 2019, the lagoon visibly collapsed, a decade after the first warnings. Three tonnes of dead fish appeared on the surface of the Mar Menor, and 4.5 tonnes more in 2021. All this was due to changing ecological conditions, which caused the destabilisation of oxygen levels in the water. The lagoon had lost resilience against extreme weather events, be it a cutoff low or a heat wave.

From environmental crisis to sustainable development

An initially environmental problem evolved into serious, entrenched and seemingly irresolvable conflicts of interest. These escalated to different levels:

- On the social level, with large protests by the population.

- On the economic level, affecting the economies of certain sectors, collapsing the local tourism trade, impoverishing the population, with trade collapsing and property prices falling.

- On the political level, the conflict has been used as a tactical tool to manipulate political opponents, at the local and regional scales, and rapidly at the national sphere, even directly affecting ministers with accusations of decisions taken decades before they were in office.

The Mar Menor is currently suffering from a socio-economic and environmental crisis, in a region with a high rate of poverty and risk of social exclusion.

Solutions that seemed good and understandable a few decades ago, as people had the right to improve their standard of living and their future, do not seem so good now. After several decades, we can quantify the impact of many decisions taken in the past and learn from them.

This situation is almost a carbon copy of similar scenarios around the world. For example, the eutrophication of the Baltic Sea and Tampa Bay in Florida. It is as important to understand what happened as it is to get out of the guilt loop. We need to build solutions that help overcome barriers to more sustainable development. As difficult as it may be, we have a unique opportunity to turn this environmental and social crisis into a sustainable development scenario for all sectors.

The search for solutions requires building understanding between sectors, availability of objective information and quantification of impacts. Key to this are: participation, mutual learning and the search for common values, to motivate and support the transition of all actors.

Overcoming barriers to conflict resolution

In environmental problems, such as the case of the Mar Menor, there is often sufficient scientific and technical knowledge to identify solutions. However, there are also social, economic, cultural and institutional barriers that hinder the implementation of these solutions. It is crucial to identify what these barriers are and how we can overcome them.

Environmental psychology and sociology are progressively making inroads as tools to understand and assist in the resolution of environmental conflicts and the adoption of solutions in a negotiated -at best consensual- way.

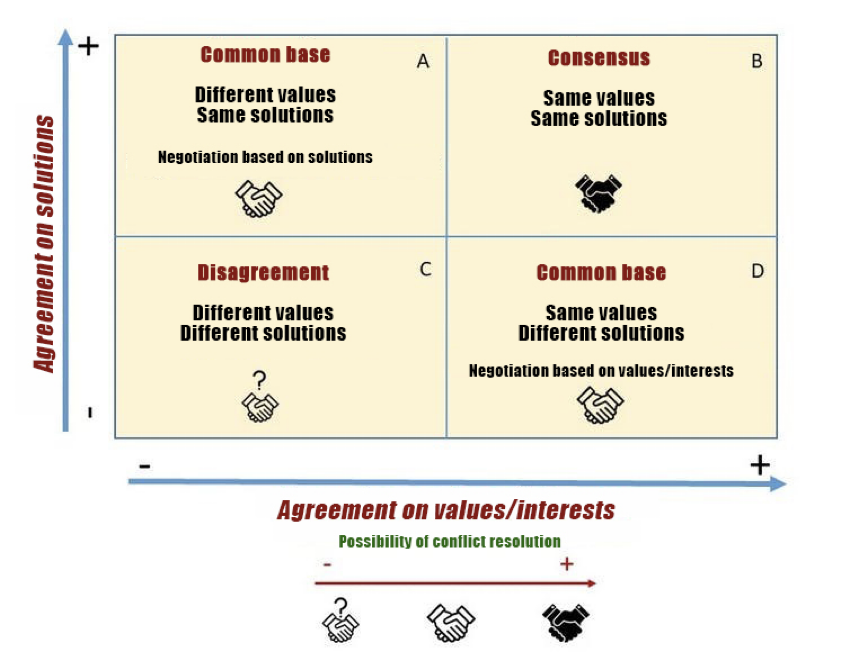

Observing and scrutinising the values behind the decisions made by different social actors allows us to identify what unites and divides the different interests of each group. The values and beliefs we hold as individuals and those we defend as a group move us to action and support our commitment to causes.

Environmental and socio-economic development policies and decisions can benefit from this, connecting with the values of different social actors, who will identify themselves in this connection, motivating and facilitating the adoption of solutions, minimising or even resolving conflicts.

Workshops that foster understanding

As part of the research carried out in the European COASTAL project to find consensus solutions to the problem of the Mar Menor, we applied a participatory methodology. For four years we organised workshops with representatives from all sectors where we identified, on the one hand, the personal and common values of the various social groups involved, and, on the other hand, their proposed solutions.

We found some divergences in the analysis, but many areas of convergence, both in values and in proposed solutions.

We fostered understanding between groups. We identified those solutions that were easier to implement because they had common ground. As for those that needed more negotiation, certain situations that required even more courageous decisions by the competent authorities in the case of disagreement, even if not total consensus, participation can bring positions closer together and generate greater understanding for better informed and transparent decision-making.

Participation, dialogue and integrated planning

In the initial workshops of the participatory process, for example, we individually asked all the representatives of the sectors (scientists and NGOs, administrations, farmers, fishermen and salt workers, the tourism sector and the local population) what their favourite landscape in the world was. To this question, 85% answered in a convinced and emotional way: “The Mar Menor in my childhood and youth”, highlighting a common set of values among sectors: the emotional landscape.

Deep roots, emotional worth, the recovery of natural, ethnographic and architectural capital were strongly shared values among all the social groups. These factors were just as important as others, which emerged from different roundtables, related to governance, economy, education and ecological status.

Following the analysis of the values, areas of common interest were identified and a roadmap with 4 goals and 14 solutions was co-designed. These also included a number of practical suggestions.

Examples of these proposals are the creation of green corridors, the promotion of agro-tourism, coastal and rural ecotourism, training of the agricultural sector on the use of fertilisers and the transition to organic farming.

We will not be able to achieve the sustainable development of the Mar Menor and the Campo de Cartagena region without mutual understanding among the groups involved, focusing on what unites us, generating knowledge and acceptance of what differentiates us, in order to reach lasting consensus. All of this based on ethical behaviour in the use and management of natural, cultural, social and economic capital as common goods.

Authors:

- Carolina Boix Fayos Científica titular, Centro de Edafología y Biología Aplicada del Segura (CEBAS-CSIC)

- Javier Martínez-López Investigador postdoctoral en el Departamento de Ecología (IISTA-CEAMA), Universidad de Granada

- Joris de Vente Científico titular, Centro de Edafología y Biología Aplicada del Segura (CEBAS-CSIC)

- Juan Albaladejo Montoro Profesor de investigación Ad Honorem, Centro de Edafología y Biología Aplicada del Segura (CEBAS-CSIC)

- Raquel Luján Soto Postdoctoral fellow, Centro de Edafología y Biología Aplicada del Segura (CEBAS-CSIC)